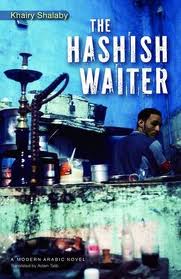

Q&A with Adam Talib, Translator of Khairy Shalaby’s ‘The Hashish Waiter’

I recently read through Adam Talib’s translation of Khairy Shalaby’s The Hashish Waiter, out this spring from AUC Press. Adam was kind enough to get into an email debate over such questions as whether Shalaby’s descriptions sometimes work at cross-purposes and what it means to sound pretentious. Read on to find out what would cause “the whole literary community” to “have a heart attack, stroke out, and soil themselves.”

I recently read through Adam Talib’s translation of Khairy Shalaby’s The Hashish Waiter, out this spring from AUC Press. Adam was kind enough to get into an email debate over such questions as whether Shalaby’s descriptions sometimes work at cross-purposes and what it means to sound pretentious. Read on to find out what would cause “the whole literary community” to “have a heart attack, stroke out, and soil themselves.”

ArabLit: How would you describe the novel in an elevator pitch?

Adam Talib: The Hashish Waiter is about escape: everyone is trying to find a way out of the stresses and strains on their lives be they financial, familial, societal, professional, etc. Khairy paints a compelling picture of a wide variety of characters, some of whom are dirt poor and others with money coming out their ears, as they all try to conquer the psychological, existential, and material concerns that they can never seem to shake. It’s not a pessimistic novel, but he wants to remind the reader that society’s out there pushing back at you and your dreams and that you can’t expect to get what you want without a fight. The characters in this novel discover that friendship and commiseration is the best defense. Despite all their different personalities, incomes, intellects, and ambitions they’re all drawn to Rowdy Salih precisely because he shows them how to fight back against society and all its rules. In that little marginal realm, off the radar, under the nose of the cops, and yet still right in the heart of downtown Cairo, the hash den is an escape, and I don’t just mean for getting high. Of course, getting high is important—it’s one of the oldest relaxation techniques in human history and an important part of social life in Egypt and much of the rest of the world—but there’s more to the den and to Rowdy Salih than hashish. In the den, everyone is equal. It’s the original ‘third place‘, an escape from the pressures of work and home, and so it’s no surprise that Rowdy Salih should be its unofficial leader as that’s precisely his whole life’s mission.

AL: What do you enjoy (and what did you find resistant, difficult) about Shalaby’s prose in صالح هيصة?

AT: They’re not actually two separate categories! The most enjoyable—and the most difficult—thing about Khairy’s prose is the way he mixes language levels (registers) within a single sentence or paragraph. Khairy doesn’t go in for the prophetic or philosophical or pompous-sounding stuff…and he really seems to be having a lot of fun when he writes. It’s difficult to constantly switch back and forth between levels of language (from ‘coarse’ street talk to the really touching and captivating poetic descriptions he sprinkles throughout the book) and part of the problem is English.

I mean English’s rich enough as a language, don’t get me wrong, but Arabic’s two languages–gross simplification alert!–and if you’re a serious talent like Khairy, who lets his characters speak and puts his own ego to the side, you can do some serious weaving and layering with idiom and tone. How to represent this multifaceted language in English is a serious challenge, partially because authors who do this in English rely exclusively on regional speech. Don’t forget, too, that the characters in the novel are dizzyingly multi-cultural: there are Egyptians, Europeans, Gulf Arabs, and there’s a wide variety among the Egyptian characters—from the highly educated to the urban poor to rural farmers.

AL: I guess I’m not sure what you mean by prophetic or philosophical or pompous sounding.

AT: Yeah, what do I mean? I guess what I’m trying to say is that Khairy doesn’t spend a lot of time looking up from the story. He doesn’t look over his shoulder like some writers and he doesn’t spend too much energy worrying about what ‘the critics’ will say. I haven’t asked him but I’m fairly certain he’s never spent a second thinking about how this might sound when it’s translated. I actually quite enjoy Camus / Sartre kinds of books where the writer uses a narrative to discuss philosophical themes or get across a mood and there are lots of Arabic examples (Sonallah Ibrahim’s very famous The Committee is at the top of the list, and I think Cairo Swan Song would fall into this category). In many ways, Arabic novels are still having a conversation with the culture at large—they’re very engaged—and it’s reflected in this style of novel. Khairy Shalaby is an important artist and also a very good critic, but he doesn’t go in for that sort of thing. Like Yusuf al-Qa’eed, Khairy tries to show that novels don’t have to be explicitly intellectual, or about intellectuals, to handle important political and social questions in a very sophisticated way.

AL: So you said earlier that the “bong” was one of the particular challenges of translating the novel. After reading it, I’d have thought you’d have said “rowdy.”

AT: Rowdy and rowdiness are the words used throughout the book for هيسة و تهييس. These are quite key terms in the book, obviously, so that’s why it was so difficult to find an English equivalent (rowdy didn’t come to me until about 9 months into the project!)

AL: Sometimes the physical descriptions of characters in The Hashish Waiter are pretty over-the-top. Hakeem’s smile, “trapped between the corners of his mouth” and where we see it “defy its shackles” and “plan its escape” works for me. But at times the descriptions get too squirrely: “the scowl on his face looked like a round loaf of bread when the loaf gets knotted up before it goes in the oven and it comes out scarred by long grooves; he looked to all the world like an ape, hissing and baring its teeth.” (Is he a loaf of bread or an ape?) How did you parse the long bouts of physical description?

AT: Well, I don’t want to start a controversy in the translation community, but I think generally the reason there are so many complex descriptions in my translations, which I acknowledge strike English-speaking readers as ‘too squirrely’ sometimes, is that other translators—consciously or subconsciously—edit, curtail, minimize, condense, or simply skip over this very familiar and very rich aspect of Arabic prose. In many ways, it’s easiest to be a translator because you don’t have to take explicit stands on artistic controversies of the day, but I think anyone who reads my translations will see where I come down on the MFA-program-inspired minimalism du jour. If the shoe were on the other foot—or to be more specific, if I were translating out of the hegemonic language rather than into it—people would inevitably be more respectful of the specific and long-standing tradition of Arabic literary prose. If an Arab came along and translated Joyce’s Ulysses and ‘edited’ it or cut some of the descriptions or toned down the long digressions, the whole literary community would simultaneously have a heart attack, stroke out, and soil themselves; and with good reason. And the loudest objections would come from Arab literary circles.

If the novels I translate read unfamiliarly, and if the descriptions seem peculiar and ‘too squirrely’ that’s partially my fault as my authorial tools aren’t as mature as the authors I translate, but it’s also true that if you compare contemporary American fiction, for example, to novels around the world and to the history of the English novel itself, Arabic novels are well within the mainstream; it’s Stephen King-inspired, adverb-hating American mediocrity that’s drifted off into an ekphrastic wasteland and then, looking over its shoulder, is astonished that the rest of the world isn’t following happily behind them! Arabic fiction has far more in common with Melville, Salman Rushdie, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Cormac McCarthy, and even Virginia Woolf than all those dessicated and neat novels produced yearly by the ton, which make less of an impression than a good sandwich.

AL: Do you find that one of Shalaby’s particular interests is the play of “different Arabics,” as with the play of different Arabs? Do you think he’s interested in the language per se, or in how language usage shapes character/class/social position?

AT: Certainly. There’s no question that Khairy pays a lot of attention to (and has a lot of fun with) shifts in levels of language (register). Language in The Hashish Waiter serves a whole host of purposes. It identifies certain important demographic characteristics as you’ve mentioned: class, education, social position, gender, region, etc. But it does a lot more than that. The Hashish Waiter is also about the shift in society that takes place in Egypt and Egyptian society and culture over the middle of the 20th century, from the monarchy and the British occupation to Nasser to Sadat (30s–80s).

The novel is told from a revolutionary, nationalist, post-colonial perspective (and there’s a lot of that heady post-independence debate, controversy, and euphoria in the novel), but Khairy uses language very cleverly to reflect not only how time changes, but how characters and the culture change. The way a character speaks or is described tells you a great deal about where they stand in the society, whether they’re at the vanguard or stuck in the past, etc.

AL: I feel echoes of Mekkawi Said’s Cairo Swan Song here. Do you think you were attracted to the two books because of similarities—both, in some ways, are novels of “the Egyptian street” and Egyptians’ interactions with foreign powers. Do you see connections between the two?

AT: There’s no question that The Hashish Waiter and Cairo Swan Song are both novels about downtown Cairo and I don’t just mean that they’re set in downtown Cairo. Downtown Cairo isn’t just the enduring political, cultural, and commercial center of one of the world’s largest and most fascinating capital cities, it’s also the only place in the city where all the different sectors of society meet. Downtown Cairo is actually not very big, but it’s highly concentrated and constantly buzzing—and as the world now knows—it’s got one of the most dramatic settings of any urban stage. …. Downtown Cairo is so fascinating precisely because it doesn’t have too many monuments—there’s no Pearl to destroy like in Manama, Bahrain, there’s no stone monument to stand in front of like an idiot and take a photo—it’s a web of streets, alleys, sidewalks, squares, and doorsteps and it’s configured for a hundred different purposes. There are bright, lit-up, loud, and happy places to see and be seen, there are the cozy cafes where you go every day to sit and breathe, read a newspaper and catch up with friends, there are bars of every kind: from the male-only, no frills saloon-feeling slices of a dying way of life, to the dancing, drinking spots for the jet-set, to the male-only gay hangouts that spring up and disappear, there are working mosques and churches, and a heavily-guarded synagogue, there are fantastic beaux-arts buildings, there is a young, but thriving, art scene, and there’s every variety of Egyptian and international life-form you can fit into something like 1 square kilometer. And we’re not even talking about the other historic, dense, and lively district of the city just bordering downtown Cairo where Naguib Mahfouz created his abundant literary worlds.

That’s why novels like The Hashish Waiter, Cairo Swan Song, The Yacoubian Building, etc. can have so much fun. They don’t have to range over a wide geographical area and manufacture distant social connections to recreate something like global diversity within the novel. Anyone who was in Tahrir Square during the days of the January 25 Revolution, or who saw it on TV screens, could see the almost kaleidoscopic variety of social life represented there, and downtown Cairo is like that on a smaller scale almost every day of the year.

The Hashish Waiter, like Cairo Swan Song, also has an eye on the wider world and especially Egypt’s position in the world.

AL: What are the main differences between your reading of the Egypt of Shalaby’s Hashish Waiter and Mekkawi Said’s Cairo Swan Song? Both are what I’d call spirited (maybe even manic) novels, although to me Hashish Waiter has a much keener sense of humor.

AT: I think you make an excellent point in a post you made on your blog about ‘novels that predicted the revolution‘. Obviously every scrap of writing, song, art from the past decade is going to be viewed in a new way now, ex post facto, but we’d be doing a great disservice to the hundreds who died and those who risked their lives and livelihoods, and to those who continue to push for the fulfilment of the revolution’s original demands, as well as to those who struggled and were killed, imprisoned, harassed, exiled, and silenced back before a revolution could even be imagined. Both these novels were written in Mubarak’s Egypt and they obviously reflect a certain cultural and social mood of the time. I’d encourage social scientists to take a look at Egyptian literature (as well as literature from across the region as it transforms before our eyes) for clues and evidence and to understand how one sector of society thought about the ‘state of the nation’ over time. But at the same time, I’d caution that these two novels, The Hashish Waiter and Cairo Swan Song, are written from radically different perspectives.

Both narrators are young men, childless, wifeless, fun-loving (or debauched depending on your perspective), and they have a wide variety of friends with extremely rich and diverse perspectives. (Reviewers who find this set-up ‘implausible’ must think Arabs all still live in tents). Both narrators also work in the creative sector of the economy, they’re financially comfortable—unlike 90% of their countrymen—and they live and work in the very heart of the capital—the main stage of Egyptian society. They are also both very sensitive to Egypt’s place in the world, the occupation of Palestine, and American hegemony. But the similarities really stop there.

Cairo Swan Song is the consummate Mubarak-malaise novel. It’s told from the perspective of an unstable, unreliable, depressed, and despondent narrator (pre-revolutionary urban Egyptian everyman much?) who can’t understand how and why his generation went so wrong. He sees his society being torn apart by a crass and rapacious materialism and a naive and patently laughable religious fundamentalism. Every hope and prospect has dried up and society itself seems to be cannibalizing itself. The overwhelming (and growing) number of homeless children in Cairo is perhaps the most striking symbol of the decline in Egyptian society. It isn’t simply that a society that so prides itself on family cohesion, neighborliness, and charity has abandoned tens of thousands of children, it’s that the government feels no responsibility at all and takes no action except perhaps exploiting the children as paid thugs (hey, foreshadowing!) to break up protests. What’s worse is that Mustafa, the narrator, doesn’t know whether making a film about the children will help solve the problem or will just end up enriching the Americans who use Egypt as a laboratory for ‘finding themselves’ or ‘spreading American values abroad’.

The Hashish Waiter was written during the Mubarak-malaise but it’s set in the early 70s. You can actually see the post-1967 cynicism overshadowing the heady revolutionary sentiments. Khairy does a wonderful job of capturing all the vibrant cultural and social trends in this period: the philosophers, writers, the lure of communism, Arab nationalism (and its demise), etc. The novel is set in the last days of the socialist, and non-aligned, experiment in Egypt and it’s easy to see how much optimism and cultural energy those policies inspired. The novel concludes with a look toward what followed Sadat, Camp David, the rise of the Baath, and economic ‘liberalization’ and it’s a decidedly sour picture. I think it’s a wonderful coincidence (as well as a great honor for me) that the translation of this novel should be published in a liberated Cairo a mere six months after the most important world revolution in three decades. It’s inevitable that the translation will be read in a different spirit from the Arabic original published a decade ago and thank god for that!

AL: From The Hashish Waiter, regarding Sami al-Droubi’s translation of War and Peace, one of the characters says: “People who’ve read it say it’s better than Edwar’s translation because al-Droubi was able to capture Tolstoy’s style, too, whereas Edwar translated the book in his own style, which means what you’re reading now is the Edwar of High Walls and not Tolstoy.” Did you worry about this being Adam Talib, or do you feel that you’ve rebuilt Khairy Shalaby in English?

AT: Edwar al-Kharrat is a serious novelist so that’s why there’s a danger of his style overpowering his translation. I’m just a hack.

AL: Would you translate more Shalaby?

AT: In a heartbeat….

Tomorrow, a Q & A with Michael Cooperson about literary time travel and Khairy Shalaby’s The Time Travels of the Man Who Sold Pickles and Sweets. Thanks to Adam for the suggestion.

Q&A with Michael Cooperson, Translator of Shalaby’s ‘Time Travels’ | Arabic Literature (in English)

July 9, 2011 @ 6:26 am

[…] Arabic Literature (in English) Skip to content HomeAboutReviewsBook ClubsForthcomingInternational Prize for Arabic FictionTop 105 ← Q&A with Adam Talib, Translator of Khairy Shalaby’s ‘The Hashish Waiter&… […]

July 9, 2011 @ 4:15 pm

Thank you Marcia for this interview. It’s been really helpful as it feeds rght into questions and quandaries currently swirling around my head with the project I’m working on. I thought you asked really good questions and I found Adam Talib’s answers both thoughtful and refreshing.

You are so good at what you do. And I am your devoted admirer!!!

:~)

July 9, 2011 @ 4:34 pm

Itinerant cook! Are you starting a blog? I just spent what seemed like forever deveining shrimp that I think are bad. Sigh.

Q&A with Adam Talib, Translator of ‘The Hashish Waiter’ | Art, Culture, Egypt, Entertainment | Arab Stands

July 10, 2011 @ 2:35 pm

[…] Q&A with Adam Talib, Translator of ‘The Hashish Waiter’ Tweet stLight.options({publisher:''});emailBy mlynxqualey- Arabic Literature (in English) […]

‘The Hashish Waiter’: Freedom and Escape in the Era of Camp David | Arabic Literature (in English)

August 29, 2011 @ 7:28 am

[…] Adam Talib and published by AUC Press this year. For those interested, last month we also ran a Q&A with Talib. The […]